Erik on product management and such

Why Super Apps took off in China

Why do China’s internet users prefer Super Apps that bundle numerous related and unrelated services into one app, over specialized single-use apps? That’s a trick question; they don’t. The emergence of super apps in China is entirely driven by commercial forces and to understand it, we need to trace back to the early 2010s when the smartphone became the portal to the internet for 700 million new internet users and the immense competition that brought to the internet sector. Once we understand the history of competition between China’s first and second generation tech giants, we will understand that Super Apps are not a user preference but the digital embodiment of digital conglomerates looking to bootstrap new services with the userbase from existing services.

A billion new internet users

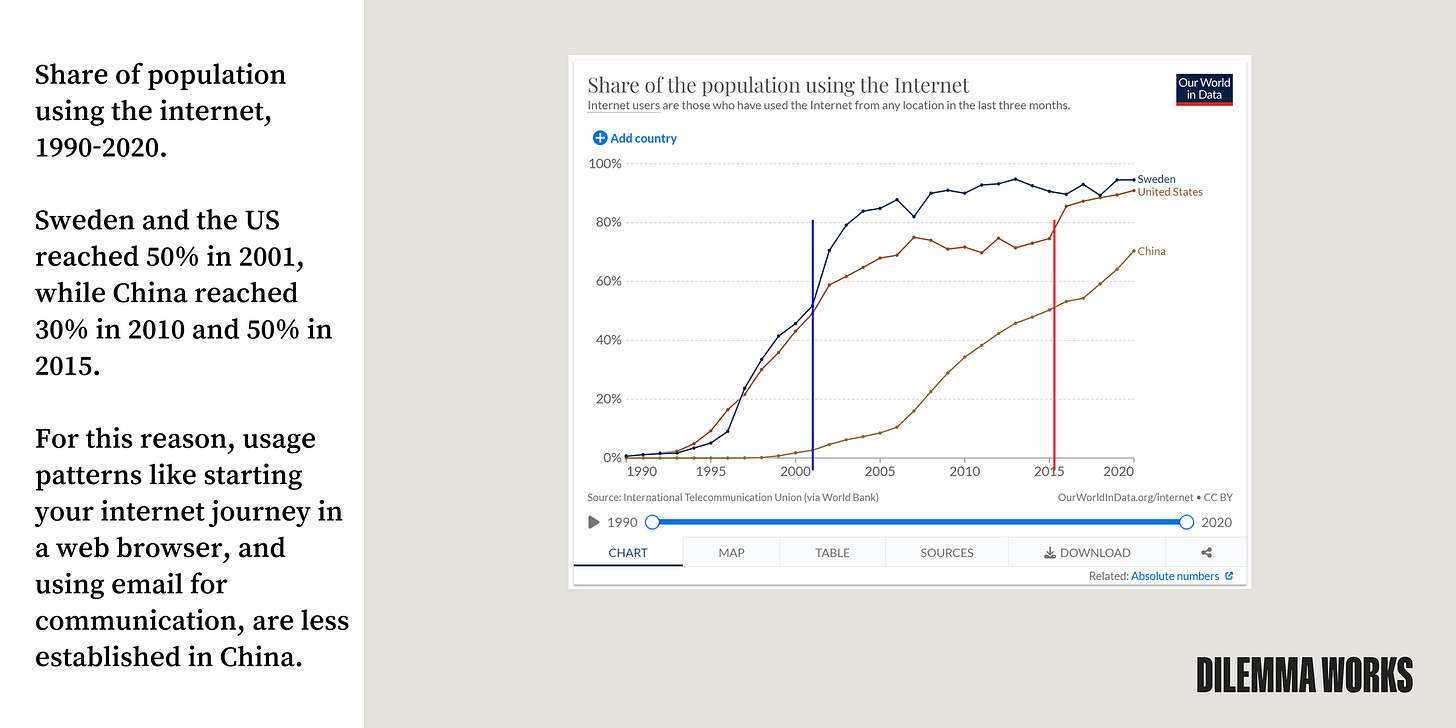

In most Western countries, internet adoption began with desktop computers in the 1990s. China’s mainstream internet users mostly skipped that stage. For the majority of China’s population, the smartphone was their first and at the time, often their only personal computing device. As of 2010, internet penetration in China remained under 35%, and mobile networks were only just becoming widespread. In Western Europe and the US, internet penetration reached 50% in around 2001. China would not hit 50% until 2015, which is when we can say that the internet really went mainstream.

This meant that, when mobile apps arrived, there was little entrenched behavior around web browsers, email, or desktop-first search. If you’ve worked in China or in a Chinese company, you will know that people in China rarely check their email. The information that you would send in an email is instead handled by mobile-first channels like WeChat and SMS or a variety of Teams-like office communication apps in China.

Living in Beijing at the time, I bought my first smartphone in the Summer of 2011 almost solely to be able to use Pleco, a specialized Mandarin dictionary app, to study vocabulary before and after my university lectures so that I would be able to understand what was going on. WeChat was launched in January 2011 but it wasn’t an instant hit. We kept using SMS to communicate even until late 2011; it was only when viral features like “drift bottle” and “shake” that let you connect with strangers nearby that my friend group first downloaded it out of curiousity, and then got hooked. Over the next few months our messaging slowly migrated from SMS to WeChat. Friend groups were set up and soon small businesses and event organizers created groups with a max capacity of 500 users to promote their activities.

To improve on the way businesses were using user groups, Official Accounts (OAs) were launched in the Summer of 2012. These OAs were used similarly to Facebook Pages; brands, stores, bands, bars and clubs would announce their latest news on their OA, and when you discovered a new cool store, the first thing you would do was to open WeChat to follow them their, as a way of bookmarking them and to be reminded of them in the future. Very few of these small businesses would have websites and they probably didn’t show up on Baidu.

WeChat Mini Programs were launched in stages from 2016 to 2017 as a natural extension of Official Accounts and Service Accounts. Brands naturally wanted to be able to not just push their messaging but also, for example, let users buy tickets to events directly in WeChat. These mini-apps were built in Tencent’s WeiXin Markup Language (WXML), a variant of HTML. This cemented WeChat’s role as a portal to the internet, or perhaps as a browser. The first thing you would do to learn more about something was often to open WeChat and see if you could find a related OA or Mini Program, and retail businesses would ask you to scan their QR code to follow their OA.

Meanwhile, Baidu, which was once China’s dominant search engine, failed to transition effectively to mobile. CEO Robin Li initially viewed the mobile internet merely as an extension of the PC era, famously stating in 2012 that the mobile internet lacked a “proven business model” and that Baidu was merely “laying out, observing, waiting, and preparing”. When information was published inside the WeChat ecosystem and specialized apps for reviews and local search like Meituan’s Dianping, that broke Baidu’s model of crawling the open internet. It lost its role as a portal to the internet, mainly to WeChat. China’s behavior for “browsing the internet” was now established as, instead of opening a browser and accessing a web search engine, opening WeChat and tapping the search bar.

By the end of the 2010s, WeChat had become much more than a messaging app. It was a payment tool, a social network, and through Mini-Programs you had the ability to access ride-hailing services, and to order or pay for lunch. But it should be noted that WeChat and Tencent provided none of these services themselves, as you would expect of a true “Super App”. They simply mediate access to the web apps that Mini-Programs are, just like Google’s Chrome does. That’s why I think a mental model of WeChat as a browser provides far more value than as a Super App, which preserves an aura of mystique around the Chinese internet rather than making it legible.

Endless blank slates

Now that we understand WeChat as a browser-equivalent, we can examine how and why other internet giants expanded horizontally and packed multiple services into the same native app.At the start of the 2010s, much of China’s digital economy was still undeveloped. Most industries had not yet built online infrastructure. Banks didn’t offer consumer-friendly online payment systems. Retail was still dominated by cash. E-commerce was new and not yet trusted.

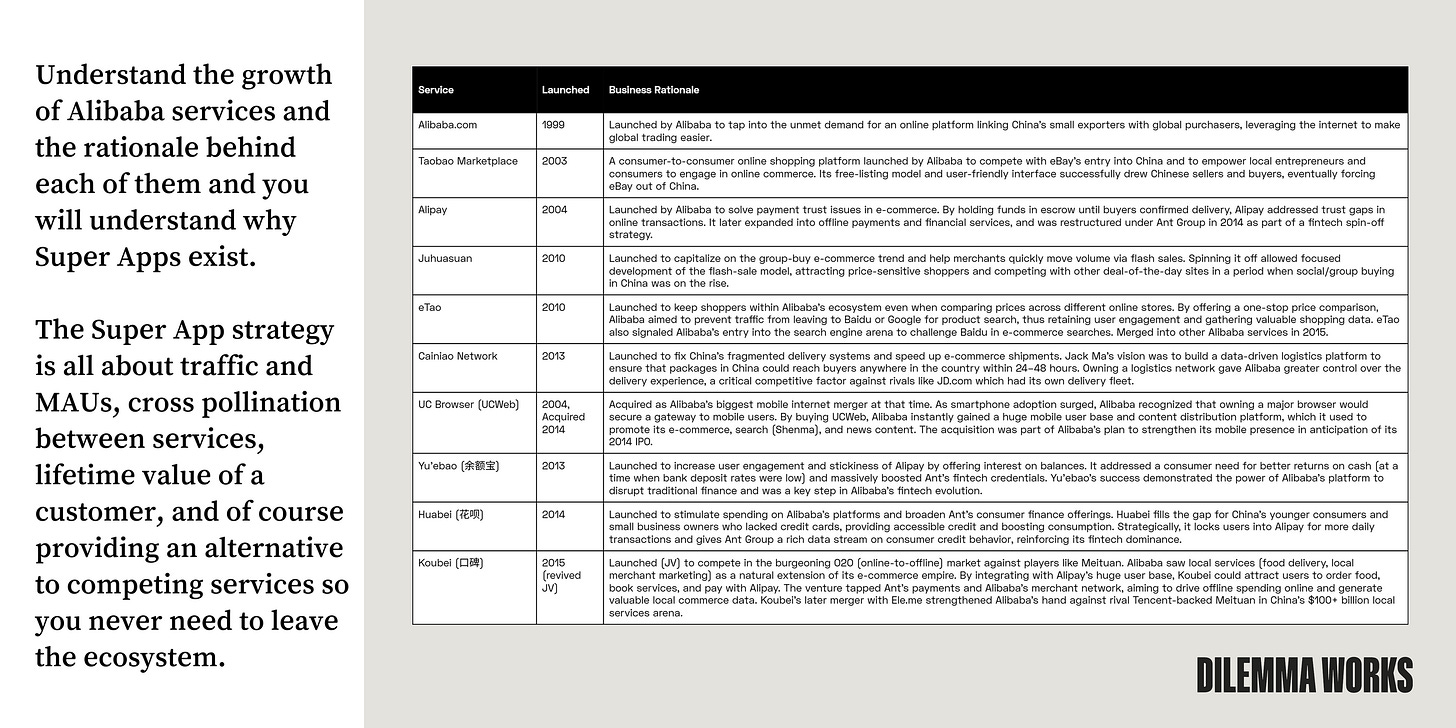

This opened a wide opportunity for ambitious internet companies. Alibaba, for example, launched Alipay to solve a simple but critical problem: Chinese banks were unwilling to hold money in escrow for small online purchases on Taobao, its e-commerce platform. Without a trusted payment layer, online marketplaces would struggle. So Alibaba built one.

Swift and reliable delivery was another pain point that needed to be solved if e-commerce was to grow and go mainstream along with smartphones. So Alibaba built Cainiao with the goal of being able to guarantee delivery within 48 hours, and and its main competitor in e-commerce, JD, launched their own logistics business.

Across the board, the logic was simple: if an adjacent service didn’t exist or wasn’t reliable, tech platforms would have to build it themselves. The upside was that they would own it and could grow it by linking it directly from their main app. It was the fastest, most efficient way to ensure the success of newly launched services because it reduced the friction of downloading yet another app and create a new account, which the majority of users would avoid doing.

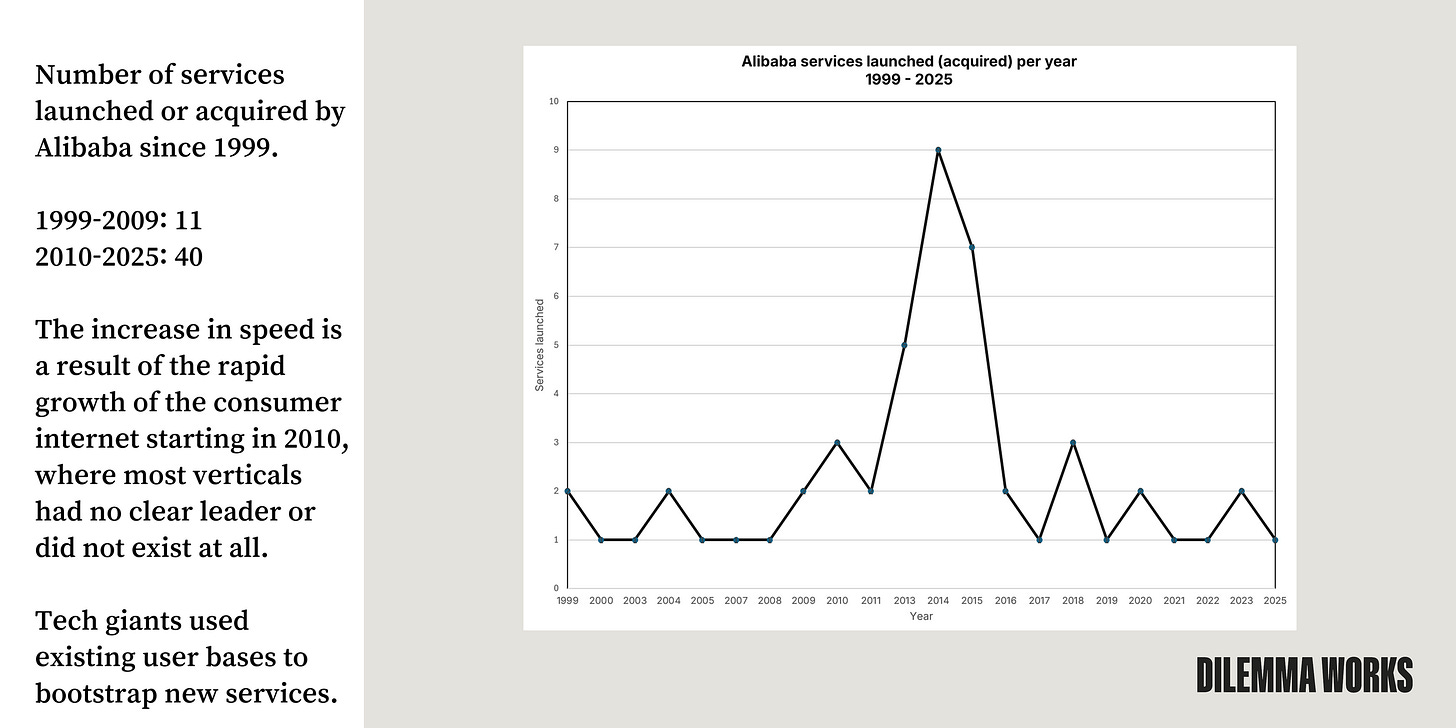

Let’s look closer at Alibaba and the services they have launched since 1999 until 2025:

From 1999-2009, they launched 11 services. From 2010-2025, they launched 41 services (I’m certain there are actually additional services I missed in my research; still the inflection point in the first half of the 2010s remains clear). This is a result of the increase in internet penetration in the Chinese population as a result of accessibly priced smartphones, and the blue ocean that the mainstream consumer internet was at the start of the 2010s. There was no clear leader in most verticals if they even existed; with their established user bases, giants like Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent saw almost unlimited opportunities to use their existing user bases to bootstrap new services.

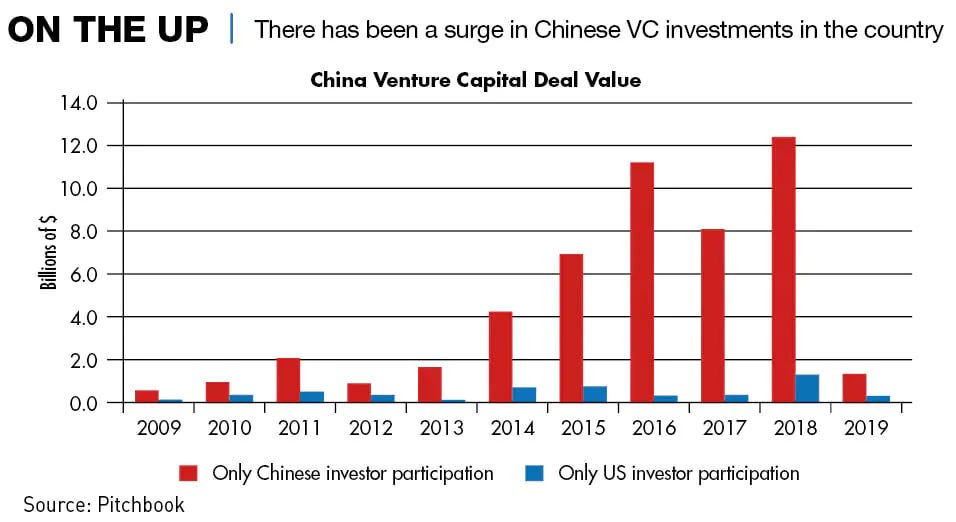

Alibaba’s increase in active services is a result of both the pressure from new venture-backed startups, and the immense opportunity that 700 million new internet users offered:

In an environment with few incumbents and minimal regulation, companies had freedom to grow horizontally, and did. With so much opportunity, you can imagine why a 996 work schedule was pushed. The idea was that you had to be first to market or you would have already lost.

Here’s a selection of services launched by Alibaba and the rationale for each launch. As you’ll see, the focus was not on providing a better user experience through a Super App, but to expand the digital conglomerate wider and faster than competitors could.

Walled gardens and private traffic

The expansion of super apps was also shaped by a more defensive tactic: limiting competition. For years, China’s internet giants Tencent, Alibaba, Baidu and later ByteDance, blocked each other’s links, services and payments inside their platforms.If a user on WeChat tried to open a shopping link from Taobao, it simply wouldn’t load. If you wanted to pay for an item on Alibaba’s platforms, WeChat Pay wasn’t an option. In effect, these companies created walled gardens, each trying to keep users inside their own ecosystems.

This encouraged platforms to bundle as many services as possible into one app. All giants aspired to evolving their flagship apps into a digital mall offering food delivery, ticket bookings, social media, and payments in-house.

Low spending power, high stakes

In the early days of the mobile internet, and still today, Chinese consumers spent less online than their Western counterparts. Their lifetime value to a single-purpose app was low, especially when compared to the US.The response from platform companies was to offer more services per user—to raise revenue without needing more users. Once a customer joined an app, companies did everything they could to keep them there: integrating games, banking, travel, and shopping.

It was also expensive to attract users in the first place. To win market share, companies gave out coupons, subsidies and even cash, as with Tencent’s now-famous red envelope campaigns to promote WeChat Pay during CNY. Once they had a user’s attention, the smartest move was to monetize them across as many touchpoints as possible, without ever sending them to a competing app.

Bundling services into one interface reduces churn and acquisition costs at the same time. If each new service is launched as a standalone app, you’ll only have a fraction of your existing userbase downloading and using the new app; probably in the low single digits in the first month after launch. You’ll then spend years trying to get them to move over to the new app by offering various discounts and other benefits. Extending the same app then becomes the obvious strategy because conversion is easily 10x higher.

It should be noted that there is nothing about this strategy that is unique to the Chinese internet. In travel, Booking.com wants to increase the lifetime value of their existing users by having them book not just their hotel stay, but also the flight, the airport transfer, tickets to attractions etc., in their app. Similarly, Uber is adding additional adjacent services to their app. What is unique to China is the timeline and the scale of opportunity and competition.

There is no user preference for Super Apps

Most writing I see on the internet explains the emergence of Super Apps in backwards way, and state that because they exist it must be because users prefer them; that the reason they exist in Asia and not in the West is because of some mysterious “cultural preference”, as in this example:‘In the West it is all about the “user”, the singular person. While app developers want as many people as possible to use their app, it’s still a singular approach. App developers in Eastern cultures consider the user as well, but within a more social, communal, context. These are two very different mindsets.

The very nature of super apps in Asian cultures is built around communal activities. Societal acceptance is an important aspect of Asian cultures and there are a number of customs and norms that reflect that. The practice of using little red envelopes with small amounts of money in them is an important social custom in China and Japan, for example. This can be done digitally as well through a super app.

[...] Asian cultures aren’t into minimalism. Apps and websites are crowded and complex. That’s a cultural preference.’

This is pure conjecture. As I’ve explained above, Super Apps exist because of market conditions and business incentives. Additionally, I have suggested a mental model of Tencent’s WeChat as a browser rather than a Super App; an equivalent to Google’s Chrome. Seen through this lens, Super Apps already exist in the West but they’re called browsers. Browsers let you access all the same varied type of web app-services that WeChat does.

There is no evidence for a cultural preference for Super Apps in Asia, but lets continue to examine this further. First, there are in fact many examples of apps in China (Xiaohongshu), South Korea (Naver) and Japan (Mercari) trending towards a simpler, more measured and modern interface, aligning with global design principles.

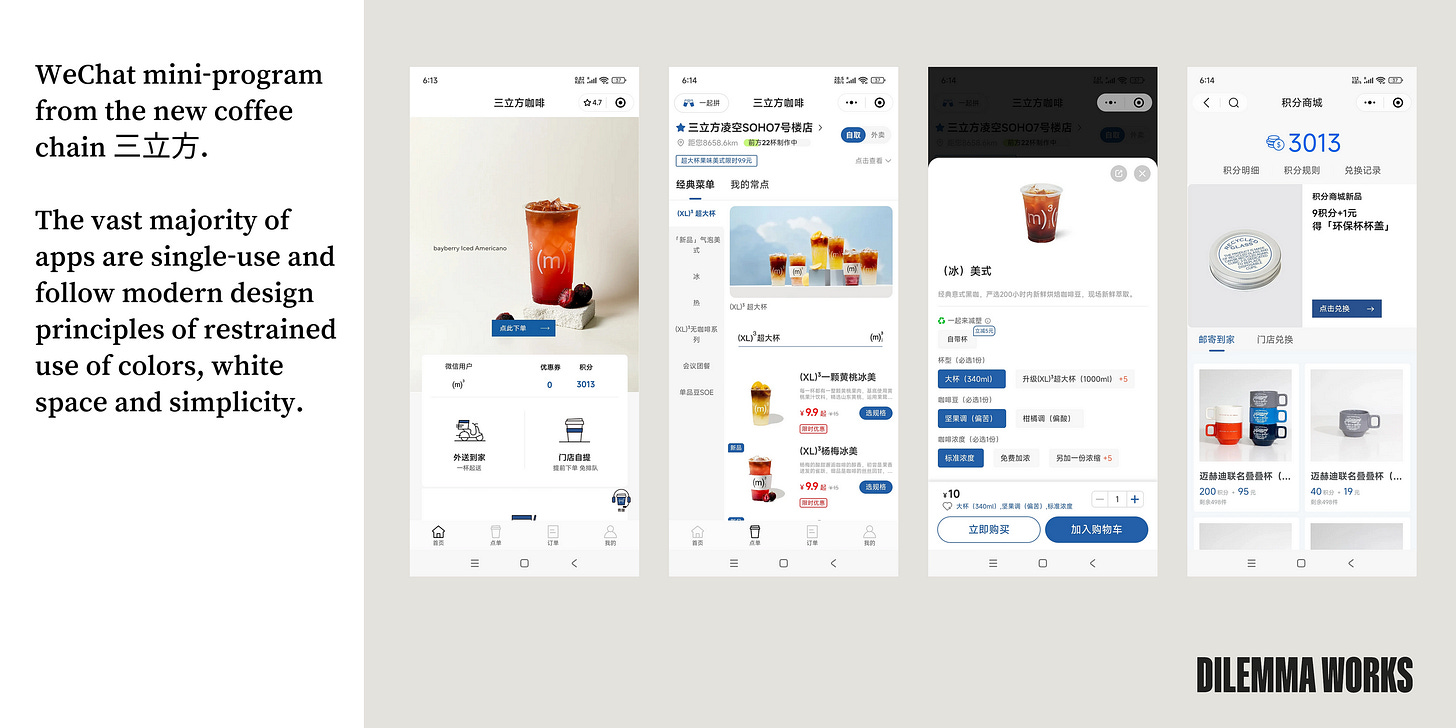

The vast majority of apps launched in China are single-use apps, in fact outside of the apps built by the few tech giants, all of them are single-use. Not only that, but increasingly we are seeing that these apps are on a trajectory towards established design principles of simplicity and focused functionality.

Closely related to the idea that users in Asia like Super Apps is the claim that “Asian users like colorful apps packed with information.” Having spent ten years in China, I have seen no evidence for that claim. In fact, at the e-commerce platform where I work, we see in our UPS that users that did not like our experience say it is because our app is “too complex”, has “unclear information”, and “too many ads”. Then why is our experience like this and why don’t we just simplify it? Because we are driven by business metrics and if you add an upsell component or a pop up, some small percentage of users will click and some will purchase. It is very hard to get organizational approval for simplification.

Similarly, in our competitor benchmark and prototype testing covering users in the US, Hong Kong, South Korea, Thailand and Japan, we’ve seen that users prefer the platform with a restrained, focused design and see it as more trustworthy.

As an example, below is the WeChat Mini-Program from a new, rapidly expanding coffee chain in Shanghai. Clean, lots of white space and restrained use of color. This is what modern apps in China look like, and what users appreciate:

The takeaway

Super apps didn’t emerge in China because users demanded them. They emerged because a set of unique market conditions—mobile-first adoption, greenfield industries, competitive blocking, and low spending power—made them a smart strategy.It also needs to be said clearly that the concept of Super Apps itself is flawed. WeChat in fact does not let you do all 10,000 things you could possible want to do on your phone. Yes, you can open links to Dianping to view restaurants, or order taxis through mini-programs, but functionality is often limited and there are frequent nudges to get you to download the native app instead.

The point of this whole thing is to understand China and its digital ecosystem not as a result of “cultural preferences” but through the hard and fast realities of economics and infrastructures that produced them.

The short version of this post is: Super Apps exist because the companies that built the services realized that cramming them into the same app helps boost business metrics, and users accept using Super Apps because that is the only way they can access said services.